Open spaces of the future that gently connect us with nature

Takanori Fukuoka

Takanori Fukuoka hails from the city of Fujisawa in Kanagawa Prefecture. He grew up surrounded by the sea and mountains, and went on to study at the Tokyo University of Agriculture in the Faculty of Agriculture’s Department of Landscape Architectural Science and the Landscape Architecture graduate course’s Urban Green Space Planning Laboratory. After graduating, he majored in landscape design at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Fine Arts and worked at landscape design firms. After doing landscape design work abroad in the United States, Europe, and Asia, he returned to Japan in 2012. I asked Prof. Fukuoka about some specific projects in Europe and the United States, which are known for being advanced in landscape design, as well as the outlook for open spaces in Japan.

Q. What made you decide to go abroad and study in the United States?

A. When I was a graduate student, I worked part-time editing a magazine called Landscape Design. I went along on an interview with a designer who was working on landscapes in the United States at the time, and that motivated me to study abroad. I feel that at Japanese universities, departments dealing with landscape design tend to be scattered across different academic disciplines, such as the faculty of agriculture or the faculty of architecture, and these fields are spread across different educational institutions, which hinders smooth communication among the individual specialist fields, even when working on-site. On the other hand, at the University of Pennsylvania where I studied, the departments of urban planning, architecture, landscape, and art are all in the same building, and there were many opportunities for collaboration.

Q. Specifically, what kind of work did you do overseas?

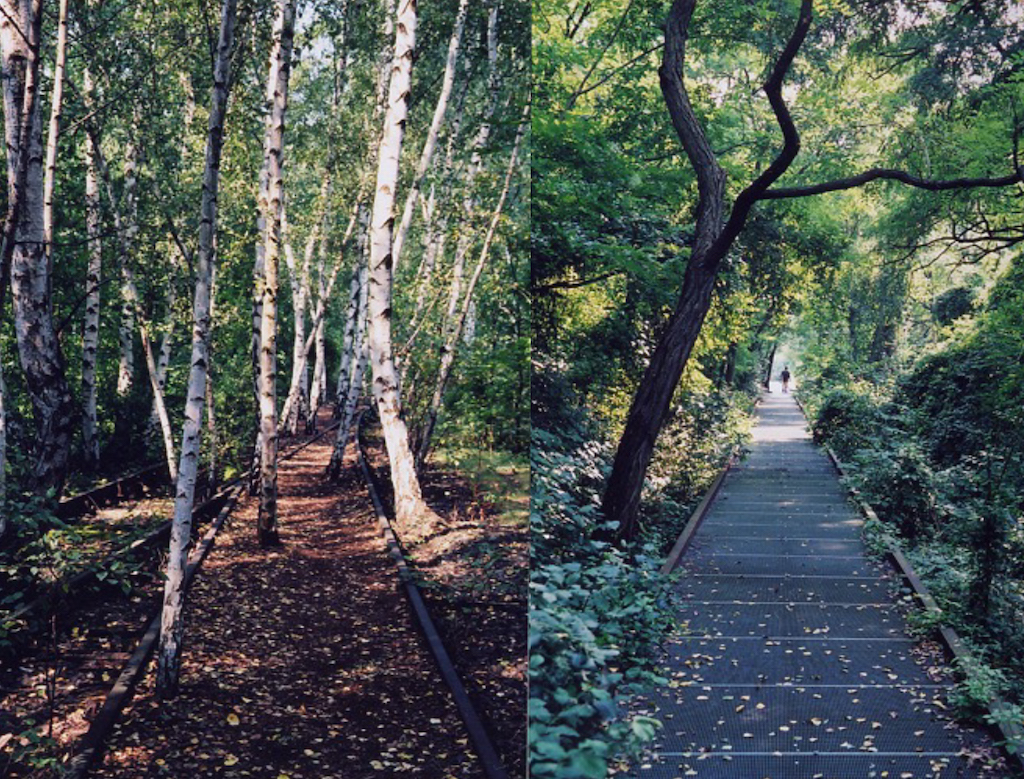

A. In the design studio at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Fine Arts, where I was enrolled from 2000, I gained experience working on landscape design for urban sites, among them former air force land and industrial, and waterfront sites in cities in Germany, South America, and North America. Specifically, these were projects to regenerate land that was declining in function, such as former factories or coal mines, through the art of landscape design. When I was selected as a travel fellow in graduate school, my research involved a project to convert an old railroad yard in the suburbs of Berlin, Germany, into a park, in which the birch grove growing on the barren land was intentionally featured and the railroad tracks were left in place to regenerate the site into a long, narrow, simple open space. I learned how to create an open space that makes use of the original topography and ecosystem while taking into consideration changes over time, rather than reducing everything to a vacant lot and then starting over.

Q. Then from 2003 you worked on larger-scale landscapes as an employee of Hargreaves Associates in San Francisco.

A. Hargreaves Associates designed open spaces for the Olympic venues in Sydney and London, and besides designing comparatively large parks and green spaces, they’re very good at environmental restoration projects to regenerate natural areas, rivers, and so on. Here I was involved in working on a sewage treatment plant. This project transformed a vehicle disposal site into a sewage treatment plant. In Japan, most people would imagine a civil engineering construction firm carrying out such work, but there a landscape design perspective was pursued. In this initiative, restorative work such as the regeneration of wetlands and rivers and rainwater purification systems was integrated with landscape design. I also found it striking that after restoration of nature had been carried out to a certain extent, scope was left for change without forcing the design to completion.

Q. So one big difference between landscape design and architecture is how changes in nature are viewed?

A. That’s right. At the Gustafson Guthrie Nichol (GGN) landscape design firm, where I worked from 2005, I found the designs very appealing for their mindfulness of the changing landscape and their gentle incorporation of the existing terrain. At this firm, the designs always sought to sculpt the land while taking advantage of the natural and geographical characteristics of each location. Tasked with designing a private residence for one of the world’s leading businesspeople, it created a place where the family could feel a connection to the land and recapture moments in time, taking full advantage of the “bones” of the land and the lake waters extending below. In Japan, open plazas are often paired with buildings, but the problem is the lack of the idea or the technology of curating the changing environment, such as plants and water, instead regarding these elements simply as building materials. It is the task of landscape design to offer a larger perspective and to make interventions in nature and landscapes.

Q. For landscapes, water is an integral element alongside plants and terrain, isn’t it?

A. Atelier Dreiseitl (now Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl) in Germany taught me the vital importance of water in cities. During the redevelopment of the site of the former Berlin Wall that used to divide East and West Germany, they created a system to store and purify rainwater. I experienced this project when I was a student, which later inspired me to work in Germany. This firm designs urban systems from a water-oriented and environmental perspective. They help create sustainable cities by collaborating with engineers on state-of-the-art technologies such as rainwater permeation, water storage, purification, and reuse. Their projects are also multinational, and I joined international teams with members from the Middle East, Asia, and Australia.

Q. The use of green open space is drawing increased attention in light of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), isn’t it?

A. Hurricane Sandy, which hit the United States in 2012, severely damaged New York City, and in response green infrastructure better adapted to climate change with tide control and urban park functions was developed. Since then, many cities have introduced green infrastructure into their parks and sidewalks to manage rainwater sustainably. In developing Japan’s cities of the future, we will need to accelerate the societal implementation of green infrastructure—for example, by striving to mitigate natural disasters through the integrated redevelopment of rivers and parks and the restructuring of roadways to encourage the temporary storage and permeation of rainwater, thus cooling cities using the shade of green spaces.

Q. After you returned to Japan in 2012, I believe that you were involved from the early stages of the Umekita 2nd Project in introducing the project team to the concepts of landscape design.

A. I did advocate the basic idea of landscape urbanism that landscape, not architecture, represents the norm for urban spaces. Unlike most building- and infrastructure-driven development, the Umekita 2nd Project is strongly conscious of how the overall landscape will look—for instance, the way it frames a park right in the center of the entire block, creates a three-dimensional outdoor space, and stays mindful of the volume and layout of buildings. In recent years, the regeneration and restructuring of cities centered on outdoor public spaces has become a global trend. Outdoor public spaces such as avenues, plazas, parks, and open spaces, as well as shared spaces such as offices, commercial facilities, and apartments, encourage people to share new experiences, thus forming a deep attachment to their cities and creating local communities. For the Umekita 2nd Project too, I think it’s important to consider the sorts of changes that utilization of open spaces will bring to the city.

Q. Courtyard Hiroo, your first project in Japan, attracted attention as a successful example of open space, didn’t it?

A. In renovating a former official residence of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the owner wanted to turn the adjacent parking lot into something like a courtyard or a public space that would make a cultural contribution and so in my design I worked to seamlessly incorporate architecture with landscape. After renovation, half of the privately-owned land was opened to the public, and the developers have been implementing what we call a placemaking approach to enhance the urban experience, so that 20,000 people a year are now attracted to the site. First Friday Tokyo, held there every month mainly by those who work on site, features outdoor fitness, food, art events, and independent summer research projects in which parents and children can participate (currently by reservation only due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

Q. Would you say that being conscious of the needs of users is important for open spaces?

A. Not only appearance, but also ease of use is an essential element of open spaces. Minami-machida Grandberry Park really embodies how we can facilitate people who use a place coming to love that place. Tsuruma Park in Machida City was separated by a roadway from a commercial facility operated by the Tokyu corporation, but we proposed a landscape-focused plan for a town that’s like a big park to be realized over a total area of about 22 hectares, connecting the private and public spaces as one. I was in charge of landscape design for the commercial, park, and park-life sites (dual public-private sites created by relocation of the former city roadway), connecting the 14 open plaza spaces established in the town like jewels on a necklace so that users could enjoy them freely.

Q. Has the flow of people changed there?

A. By connecting green open spaces from the park to the station, we expanded on the idea of a park that comes to greet you at the station. By providing a large open space inside a commercial complex, we transformed this into an integrated district with a loose but connected structure that anyone can enjoyably and safely wander from place to place in. This creates a flow from Minami-machida Station through commercial facilities, which then connects to the park and the river. This dilapidated area has been renewed and reborn with an open atmosphere, making the outer perimeter somewhere that anyone can easily go jogging or enjoy physical exercise. I believe that because the boundaries between shopping, walking, and exercise are now blurred, the degree of freedom has expanded. Beneath the ground, we also improved the infrastructure for the adjustment reservoir. Moving forward, I hope that the park, the commercial facilities, and the residents will keep working in unison to grow this over time into a town that’s like a big park. The “Minami-machida: A Town for Everyone” general incorporated foundation has been established to enable the three management entities (the park, commercial facilities, and art museum) to work together, and placemaking efforts for each site have started to cross over. My ideal is taking open spaces as the starting point, then creating livable cities in which people can live comfortably. Actually, I’m most interested in the kinds of changes that will be seen in 10 or 20 years.

Takanori Fukuoka

Associate professor at the Landscape Design and Geoinformatics Laboratory, Department of Landscape Architecture Science, Faculty of Regional Environment Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture. He also runs FD Landscape. After graduating with a major in landscape design at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate Division of Arts and Sciences, he worked as a consultant in the United States and Germany, and as a specially appointed associate professor in the Sustainable Living Environmental Design, Department of Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University. He took up his current position in April 2017. His design works include Courtyard Hiroo (Good Design Award) and Minami-machida Grandberry Park (Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Award: Cityscape Award; Green City Award), and his publications include Working Abroad in Architecture 2: Cities & Landscapes (Japanese only; Gakugei Shuppansha) and Creating a Livable City (Japanese only; Marumo Publishing).

portrait photos: KENICHI FUJIMOTO text: JUNKO KUBODERA

Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook